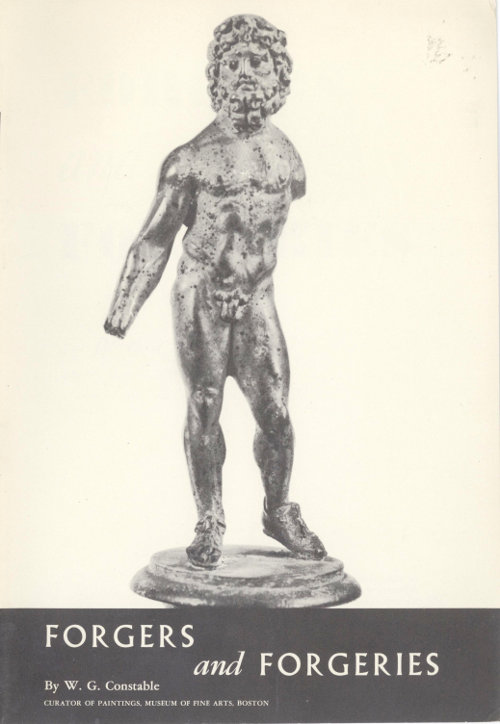

ON THE COVER PAGES

A forgery of a Greek bronze statuette (BACK COVER), anda genuine example (FRONT COVER). Such “type” forgeriesare exceptionally difficult to detect. Probably made forthe tourist trade.

Retail Price $1.00

FORGERS

and

FORGERIES

BY W. G. Constable

CURATOR OF PAINTINGS

MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS, BOSTON

ART TREASURES OF THE WORLD

NEW YORK AND TORONTO

ART TREASURES OF THE WORLD

100 SIXTH AVENUE, NEW YORK 13, N. Y.

IN CANADA: 1184 CASTLEFIELD AVENUE

TORONTO 10, ONTARIO

Printed in U. S. A. AT14 W

Copyright 1954 by Harry N. Abrams, Incorporated. Copyright in the United States and foreigncountries under International Copyright Convention. All rights reserved under Pan-AmericanConvention. No part of the contents of this book may be reproduced without the written permissionof Harry N. Abrams, Incorporated. Printed in U.S.A.

The usual idea of a forgery is of something deliberately fabricated toappear to be what it is not; something conceived in sin, and carryingthe taint of illegitimacy throughout its existence. In fact, however,many things made for quite innocent and even laudable purposes have beenused to deceive and to defraud, by means of misrepresentation or subsequentmanipulation. So the essential element in forgery lies in the way an object ispresented, rather than in the purpose that inspired its making.

Still, it is objects made to deceive which have always held the center of thestage. Without doubt, the main motive for their manufacture is to makemoney. But often there is an element of drama, even of romance, in the waythey come into existence. A famous example is a Sleeping Cupid which theyoung Michelangelo is supposed have carved in imitation of the work of classicalantiquity and which, after being buried in the ground, was bought by adealer and sold as an antique, being rated as such until its true origin was revealed.Though the element of deceit was present from the beginning, theprimary purpose of the work was a challenge to the past; and it is significantthat Michelangelo’s early biographers counted the success of the imposition to6his credit, since it proved that he could successfully rival the sculptors of Greeceand Rome.

Such challenges to the past have undoubtedly inspired men who were orultimately became professional forgers. This seems to have been the case withGiovanni Bastianini (1830-1868), the Italian sculptor. His admiration forearly Renaissance Italian sculpture bred in him a spirit of rivalry which issuedin the production of remarkable imitations to be exploited as originalsthrough collaboration with a dealer. Alceo Dossena (1878-1937) also seems tohave wanted to prove himself the equal of earlier sculpt