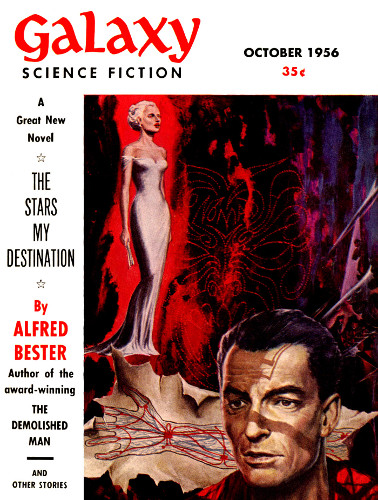

MAN OF DISTINCTION

By MICHAEL SHAARA

Illustrated By DICK FRANCIS

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Galaxy Science Fiction October 1956.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

Being unique is a matter of pride—but being

a complete mathematical impossibility?

The remarkable distinction of Thatcher Blitt did not come to theattention of a bemused world until late in the year 2180. AlthoughThatcher Blitt was, by the standards of his time, an extremelysuccessful man financially, this was not considered real distinction.Unfortunately for Blitt, it never has been.

The history books do not record the names of the most successfulmerchants of the past unless they happened by chance to have beenconnected with famous men of the time. Thus Croesus is rememberedlargely for his contributions to famous Romans and successful armies.And Haym Solomon, a similarly wealthy man, would have been longforgotten had he not also been a financial mainstay of the AmericanRevolution and consorted with famous, if impoverished, statesmen.

So if Thatcher Blitt was distinct among men, the distinction was notimmediately apparent. He was a small, gaunt, fragile man who had thekind of face and bearing that are perfect for movie crowd scenes.Absolutely forgettable. Yet Thatcher Blitt was one of the foremostbusinessmen of his time. For he was president and founder of that nobleinstitution, Genealogy, Inc.

Thatcher Blitt was not yet 25 when he made the discovery which was tomake him among the richest men of his time. His discovery was, like allgreat ones, obvious yet profound. He observed that every person had afather.

Carrying on with this thought, it followed inevitably that every fatherhad a father, and so on. In fact, thought Blitt, when you consideredthe matter rightly, everyone alive was the direct descendant of untoldnumbers of fathers, down through the ages, all descending, one afteranother, father to son. And so backward, unquestionably, into theunrecognizable and perhaps simian fathers of the past.

This thought, on the face of it not particularly profound, struckyoung Blitt like a blow. He saw that since each man had a father, andso on and so on, it ought to be possible to construct the genealogy ofevery person now alive. In short, it should be possible to trace yourfamily back, father by father, to the beginning of time.

And of course it was. For that was the era of the time scanner. Andwith a time scanner, it would be possible to document your family treewith perfect accuracy. You could find out exactly from whom you hadsprung.

And so Thatcher Blitt made his fortune. He saw clearly at the beginningwhat most of us see only now, and he patented it. He was aware not onlyof the deep-rooted sense of snobbishness that exists in many people,but also of the simple yet profound force of curiosity. Who exactly,one says to oneself, was my forty-times-great-great-grandfather? ARoman Legionary? A Viking? A pyramid builder? One of Xenophon's TenThousand? Or was he, perhaps (for it is always possible), Alexander theGreat?

Thatcher Blitt had a product to sell. And sell he did, for otherreasons that he alone had noted at the beginning. The races of mankindhave twisted and turned with incredible complexity over the years; thenumbers of people have been enormous.

With thirty thousand years in which to work, it was impossible thatthere was not, so