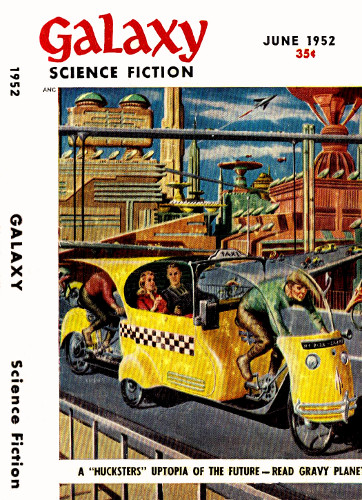

Shipping Clerk

By WILLIAM MORRISON

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Galaxy Science Fiction June 1952.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

If Ollie knew the work he was doing, he would

have resigned—if resigning were possible!

If there had ever been a time when Ollie Keith hadn't been hungry, itwas so far in the past that he couldn't remember it. He was hungry nowas he walked through the alley, his eyes shifting lusterlessly from oneheap of rubbish to the next. He was hungry through and through, allone hundred and forty pounds of him, the flesh distributed so gauntlyover his tall frame that in spots it seemed about to wear through, ashis clothes had. That it hadn't done so in forty-two years sometimesstruck Ollie as in the nature of a miracle.

He worked for a junk collector and he was unsuccessful in his presentjob, as he had been at everything else. Ollie had followed the firstpart of the rags-to-riches formula with classic exactness. He had beenborn to rags, and then, as if that hadn't been enough, his parents haddied, and he had been left an orphan. He should have gone to the bigcity, found a job in the rich merchant's counting house, and saved thepretty daughter, acquiring her and her fortune in the process.

It hadn't worked out that way. In the orphanage where he had spent somany unhappy years, both his food and his education had been skimped.He had later been hired out to a farmer, but he hadn't been strongenough for farm labor, and he had been sent back.

His life since then had followed an unhappy pattern. Lacking strengthand skill, he had been unable to find and hold a good job. Without agood job, he had been unable to pay for the food and medical care, andfor the training he would have needed to acquire strength and skill.Once, in the search for food and training, he had offered himself tothe Army, but the doctors who examined him had quickly turned thumbsdown, and the Army had rejected him with contempt. They wanted betterhuman material than that.

How he had managed to survive at all to the present was anothermiracle. By this time, of course, he knew, as the radio comic put it,that he wasn't long for this world. And to make the passage to anotherworld even easier, he had taken to drink. Rot gut stilled the pangs ofhunger even more effectively than inadequate food did. And it gavehim the first moments of happiness, spurious though they were, that hecould remember.

Now, as he sought through the heaps of rubbish for usable rags orredeemable milk bottles, his eyes lighted on something unexpected.Right at the edge of the curb lay a small nut, species indeterminate.If he had his usual luck, it would turn out to be withered inside, butat least he could hope for the best.

He picked up the nut, banged it futilely against the ground, and thenlooked around for a rock with which to crack it. None was in sight.Rather fearfully, he put it in his mouth and tried to crack it betweenhis teeth. His teeth were in as poor condition as the rest of him, andthe chances were that they would crack before the nut did.

The nut slipped and Ollie gurgled, threw his hands into the air andalmost choked. Then he got it out of his windpipe and, a second later,breathed easily. The nut was in his stomach, still uncracked. AndOllie, it seemed to him, was hungrier than ever.

The alley was a failure. His life had been a progression from rags torags, and